Smithsonian Folkways Music

You may not know Chip Taylor by name, but you’ve certainly heard his work. As the writer behind a tall stack of hits for a list of artists that includes Willie Nelson, Bobby Fuller, Emmylou Harris, and Waylon Jennings — not to mention “Angel in the Morning” and the stone-cold classic “Wild Thing” — Taylor has been part of rock’s DNA almost from the beginning. Now he’s moving on to a new phase of his career, as the frontman for Chip Taylor & the Grandkids.

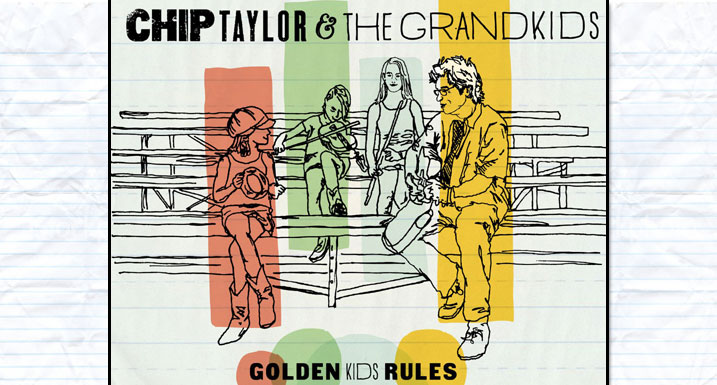

The project is exactly what it sounds like: Taylor, guitar in hand, fronting his three grandkids. It’s an adorable idea, but it’s also a pretty terrific album, grounded in Taylor’s trademark earthy (or, as he might put it, “sweaty”) aesthetic while still filled with all the carefree whimsy and lovely harmonies any kindie fan could hope for. Golden Kids Rules is out today, and you need to hear it — but first, read Taylor’s thoughts on the album and his long, storied career.

This is a really enjoyable album, and it’s also a really beautiful idea — in theory, anyway. I imagine there must have been a few moments when trying to make a record with small children seemed like more trouble than it was worth.

[Laughs] The whole thing was totally a labor love. The whole idea at the start was to surprise their uncle for his wedding, so I wrote a couple of songs and talked to the kids, and they seemed really excited. But yeah, it’s hard to get the three of them to focus on something for an extended period of time. It wasn’t easy, but they always liked the results. It was never one of those things where they didn’t want to do it again, but it was funny watching their attention wander all over the place.

And, you know, I’m the grandfather, but this wasn’t like just going out in the field and having fun; there were times when we had to buckle down. And little Sam, for instance, would pout and not want to sing, so I’d have to sit down with her and say “If I go in there with you, will you do it?”

We did our first big performance at the Smithsonian Folkways Festival a few months ago. We’d been rehearsing, but we hadn’t performed for anyone, and every week I’d go up there for an hour to work with them. You just never know what you’re going to get with kids. [Chuckles] One comes in and she can’t hardly move, she just wants to lay on the couch. I just love them so much, and they like working with me, so that makes it easier. The good thing I did, I think, is that when I rehearsed with them, I’d get everyone in their spot and I’d pretend my band was with me, playing. I’d talk to them — “John, will you pay attention back there? Tony, let’s go. One, two…” I’d get them going like that, so the kids would get the feel.

It was good, because when we did the festival, we ended up not being able to do a soundcheck. Right beforehand, I’d told the kids, “You’re each going to have your own microphone, and you have to soundcheck on it. You do it like this — ‘testing, one, two, three; testing, one, two’…you’ll have to tell us whether you’re hearing enough of your own voice.” Then when we got up there, they only gave us five minutes to set up, and all these people were in the audience — the place was packed — and we got up on the stage, I counted off with the band, and one of the girls walked up to her mic and said, “Testing, one, two…” [Laughs]

So I told the audience, “We’re just going to do a little part of one song here — this isn’t really part of the performance yet.” So we did our little warmup, and when it was over, all the people started cheering. That was it. The girls were like, “Oh, this is what it’s all about.”

But the whole thing of working with the kids — that’s part of the fun of it. It’s never perfect. You’ve got three kids with three different personalities, and they’re all thinking about different things. Underneath it all, they all want it to be good, but it’s about working through that, and working through your own emotions. That’s the fun of it. And it’s fun to hear them talk about what their problems are: “Okay, Kate, why do you have to lie on the sofa all day today?”

“Well, Peepaw, this is what I did today…”

“Well, you have to get through that, my dear.” It’s that wonderful back-and-forth where you have to work things out together.

I know you’ve said you didn’t come from a musical family, and I know that — at least according to some of what you’ve said in other interviews — you originally didn’t even intend to be a musician.

Well, what it was — I didn’t come from a musical family, at least insofar as my mom and dad didn’t play any instruments. But they loved the arts. We loved going to movies, listening to singers like Bing Crosby and stuff like that. So it was floating around the house, but what really got me going was when my parents took me to a musical in New York — My Wild Irish Rose. I didn’t want to go, but they couldn’t find a babysitter — I was seven or eight years old. All I remember feeling is that when I heard the music start — heard that orchestra start, right up against it, watching those people create that sound — I got a real buzz. It was like when you fall in love for the first time and you don’t want anyone interrupting your feeling. That was it. We had an hourlong drive back home, and I didn’t want my parents to talk. I just wanted to keep feeling that feeling, and I knew I wanted that to be my life. That’s always been a part of me, and all of my career decisions have been based on that feeling.

That’s what it was like for me when I discovered country music for the first time. You know, it was the sadness that I liked. The warm thing that…the pedal steel playing, you know? I never liked that clicky, poppy stuff. On this record with the kids, we did a song called “Quarter Moon Shining,” and that carries some of that tone. Same with “Magical Horse.” It’s got an honest kind of thing to it. That’s the way I talk to the kids about music, and they love it.

Do you see some of that ambition starting to take root in your grandchildren?

You know, these days, there are so many things kids do. Every minute of the day, they have some activity that they’re going to, and they usually like all of them, but I don’t know if they have enough time to think about what they really want to do. I don’t know that they know that yet, and I don’t know that they’re given a chance to know. Their lives are so filled.

It’s all healthy — swimming, basketball, soccer, band, and all that good stuff. But do they love one more than another? I don’t know. They sure do love performing, though. They love the applause, and the idea that they sounded good.

You’ve seen the best and the worst of the music industry, and you got started at a relatively young age. Is there a limit to how big you’re willing to let this project get?

I don’t have concerns about it. I see such beautiful things in these kids, and they aren’t spoiled by this kind of attention. I’m not worried. Every once in awhile, my wife or the kids’ mother will say something to the effect of, “I don’t want them to grow up like so-and-so young star,” but I can’t see that happening. I know we want to keep doing it. Lately, whenever we’re together, singing or just kind of fooling around, when something silly happens I’ll start writing a song about it. I’ll start to sing, but I’ll leave lines open for one of them to add something, and before you know it, we’ll have a song. They love doing that, and if we get the chance to make another album after this one, it’ll include more co-writing. What a wonderful thing that is.

I think for a lot of artists, it might be frustrating to be so identified with one of your earliest, simplest songs…

You’re talking about “Wild Thing.”

Right. But you seem to have used that simplicity as a lesson, particularly on this album.

Well, I’m a simple guy. [Laughter] When I was younger, the songs I liked the most were the ones that just got to the heart of things. I never liked clever ones at all. Anything that sounds too worked-on, I don’t like. The early country singers, and guys like Elvis — they were just singing with real emotion. So when I started writing, you know, my first hits were for Willie Nelson, Eddy Arnold, the Brown Family, and Waylon — I wrote for people like that before I started rockin’. “Angel of the Morning” might have a few more chords in it, but it has a very honest movement. It just goes where it goes. I felt a chill when I wrote it — it was just a feeling.

And that’s “Wild Thing” — it’s just a feeling on tape. And you can play it anywhere. I remember being in this little town right above Milan, sitting near this mother and her two young kids, and I started playing that groove — the kids were bouncing back and forth. Looking at me and grooving. There’s a magic to that. I never look at it as a lesser song — it’s one of my most powerful songs.

Those chords are elemental. Putting them together must have felt like discovering fire.

It’s the way the strum goes. It’s a sweaty kind of thing — I like sweaty songs. To me, that’s one of the better ones. I loved all those covers of it. Jimi Hendrix totally got it.

It’s a song that has everything it needs, and nothing more — and I think being hardwired into music at that fundamental level might make you uniquely qualified to record music for kids.

To me, all great music is about feeling. It comes from me as the writer, but it also comes from the people you’re performing with — and for me, that’s the beauty of this album, is coming together with the energy of the kids. That’s what this represents. Their performances are wonderful, and the musicians who worked with us aren’t playing down to kids — these are soulful players, and they’re just playing songs.