Last week, Jeremy Greenfield at Digital Book World published an editorial titled “When Growth in Children’s E-Books Hits the Poverty Line.” You can read the whole thing at the link, but basically, the article points out two things:

- In general, children’s book publishers are making a lot less money from ebooks, and

- Low-income children are being deprived of access to digital content.

Both of which are demonstrably true. The first item, as Greenfield notes, is affected by a number of factors — and I’d argue that the main one is what he refers to as “the tactile nature of many children’s books.

” Put another way, I think a lot of parents don’t see the value in tablet versions of books for young children; it can be a lot more fun (and a lot easier on your electronics) if you supply them with board books that they can hold, chew on, and otherwise abuse.

Because of what I do (as well as my general fondness for gadgetry), we’ve muddled around with a few ebooks at Dadnabbit HQ — and a lot of them are quite good, whether they’re presented as “books” or “apps.” Titles like Hugless Douglas, A Duck in New York City, The Fantastic Flying Books of Morris Lessmore, and The Monster at the End of This Book are all beautifully made, and they all add a layer of interactivity that you can’t get from a paper book. I’m not saying it’s better, just different.

Animation and sound effects aside, though, my kids don’t really care. At the end of the day, they never ask for those titles at storytime — they always, without fail, pick books from the shelf. (And that includes the Kindle shelf, where I store the digital chapter books we read, like The Secret Zoo.) I don’t know if it’s because they think of those other ebooks as games or just because they’d rather be read to from the paper page, but for the most part, Douglas and his friends collect digital dust.

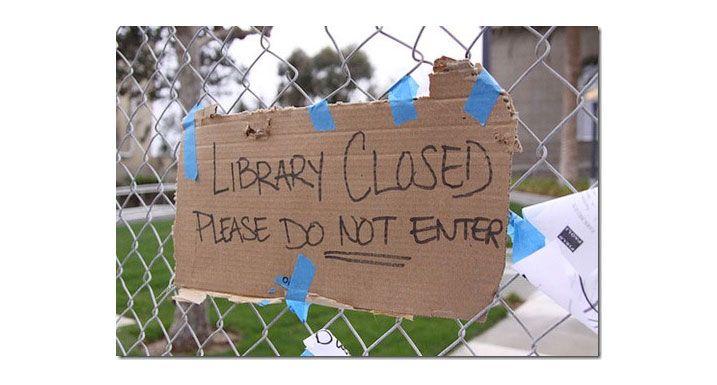

I’ve been thinking about Greenfield’s editorial a lot over the last week, and no matter how many ways I approach the issue, I’m not convinced we need to worry about this ebook poverty gap. I’m sure publishers do, but that’s another story — when it comes to low-income kids, I think what we really need to worry about is the wave of public library closings that American cities have been facing for years now. I think the health of our library system affects us all, but it really has a tremendous impact below the poverty line, and that won’t change no matter how many families manage to get their hands on an e-reader or tablet.

Again, I’m not opposed to children’s ebooks. I’m just not convinced that adding music and animation creates an essential experience that’s truly appreciably different from just sitting down and reading. I suppose you could make the argument that this is broadening the cultural divide that started to open with radio and television, and I don’t know enough to argue about the long tail effect of low-income kids being forced to catch up with their more gadget-equipped peers. It certainly seems, though, that we’re looking at the front edge of a technological shift — albeit one that doesn’t seem to be as profound as, say, the advent of home computers.

A tablet isn’t really built to teach you meaningful skills — it’s there to encourage consumption, and while (again) I’m not knocking consumption in and of itself, I’m just not convinced that lack of access to apps or ebooks constitutes a meaningful disadvantage. It can certainly be symptomatic of one, but again, I think we should be much more worried about what those symptoms indicate on a broader level.

Or maybe this is just a generational knee-jerk reaction — a bout of grumpy old man shrugging? I’m perfectly willing to concede that I may not have a firm enough grasp of the big picture here.

What do you think — is an ebook poverty gap something we need to worry about?