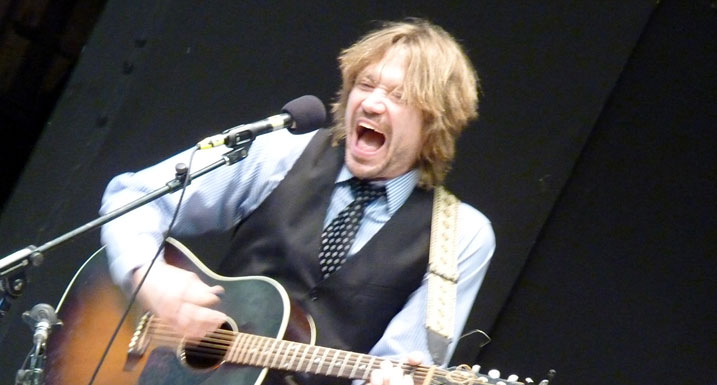

Even by the relaxed standards of kindie rock, the Deedle Deedle Dees are wild, woolly, and wonderfully eclectic, a hard-rocking crew of roots musicians who just so happen to record music that makes sense for a family audience. Once I saw them leading a crowd through a rousing singalong of “Tub-Tub-Ma-Ma-Ga-Ga,” I was hooked forever. Here, listen:

Needless to say, I’ve been waiting on tenterhooks for the Dees’ new release, Strange Dees, Indeed, and it does not disappoint — it’s a rollicking blend of history and hooks unlike anything you’ll hear anywhere else. Truly, these are strange Dees…but strange isn’t bad. In fact, in this case, it’s so, so good.

I’ve been idly talking to Lloyd Miller of the Dees about doing an interview for months now, and we finally got around to setting aside 15 minutes for a chat about the new record last week. Here’s what was said:

Aside from the fact that the new album was produced by the mighty Dean Jones, what made Strange Dees, Indeed different from your last record?

I think this record sounds more like we do as a real band. At night, we do shows that aren’t for kids — we do klezmer, and swing, and R&B, jazz, all sorts of stuff. We get pretty raucous. I talked to Bill Childs before we started recording this album, and one of the things he said was “I think the last two records were good, but they don’t really capture your live feel.”

So that’s what we were going for, and I think we got it for the most part. Not only the live sound, but the wide range of sounds we have. Songs like “The Golem” and “Mayor LaGuardia’s Stomach” — we’ve been wanting to get at those sounds for awhile now. There are a lot of different flavors in there that weren’t in the past.

I’ve heard from a number of artists that they feel a greater freedom to be eclectic for the family music audience, but you guys take that to a completely different level.

Yeah, we get bored really quickly. And Dean was good for that approach, too, because we built a lot of these songs in pieces, and he came up with a lot of new sounds. It opened up all these different options besides your standard bass, guitar, drums, and keyboards.

Well, it isn’t just musically. You cover a lot of lyrical ground that’s off the beaten path, too.

Yeah. I mean…the songs on this album have been the result of a lot of different projects we’ve been involved in over the past two years. School writing projects as well as this series of monthly variety shows we’ve hosted. Each of those shows had a different theme, so I’d write songs for them — topics like, you know, bike safety and folklore. Not everything was written that way, but these are sort of a mashup of the best of everything we’ve come up with lately.

That’s a great way of writing for an album.

I was nervous before we started, because I didn’t know what kind of kids’ record it would be. There isn’t really a big singalong number like “Nellie Bly.” I mean, kids like these songs, and they listen to them, but they don’t fit into that same sort of mold. Finally, I just accepted that these are the songs we’d written, and the songs we like. The band was really more excited about recording these songs than we’ve ever been going into an album.

My landlord is Roy Nathanson of the Jazz Passengers, and he was one of the first people I played it for. Within the first five seconds of “Phineas Gage,” he said, “This is already better than your last record. No one’s gonna buy it, but this is art. You know, Lloyd, this is not a kids’ record.” And I was like, “Yeah, I know.” And he said, “No, but that’s good!“

I want to circle back around a couple of things you’re talking about here. First, I think Bill had some sage advice for you, because the Dees have a live energy unlike anyone else on the kindie scene. It’s almost aggressive in a way.

That comes from a lot of places, including the people we play for. Last year, we played at the Many Hands release concert, and there were a lot of other artists there — you know, people like Dan Zanes and Elizabeth Mitchell. It was more of a folky vibe. We went up there and we were screaming in everyone’s face, and I realized we might need to pull it back a bit. [Laughs] We also play for a lot of crowds in New York where we’re seeing kids who are part of violence prevention programs, and they’re looking at us with our ties and wondering what we think we’re doing.

So we’re always having to prove ourselves in a way, and I’m always trying to figure out what to bring to a certain show. When we’re in a New York public school, the energy definitely has to be very high and very aggressive, just so they know we’re a real band.

There’s a bravery there, as well as in the subject matter you cover. I’ve often wondered how much blowback you get from parents who might not be comfortable with the topics you cover or the energy the band puts out.

I dressed up for Halloween this year, and people were surprised, because I don’t normally do it. I explained that it’s from my earliest days of performing for kids, when the slightest difference in my appearance could freak them out, because they expected me to always be a certain way. You know, even a hat could upset a child — “It’s okay, honey, that’s still Lloyd.” We did our first Halloween show with facepaint and costumes, and maybe it was a little scary or edgy for the kids.

But since then, no one has said anything along those lines. I definitely have…because so much of the work I do is singalongs with little kids, I definitely feel like no matter what kind of writeups the Dees ever get, people still like me as the guy who does the singalongs. There are certainly people who like the Deedle Deedle Dees, especially teachers and librarians — that market really goes for us. But in terms of the sort of high-end kindie parent market, parents come to our shows, and I can tell they wish I was sitting on the floor. I really have yet to find the commercial outlet for what we do. If I was smart, what I would do all the time would be birthday parties and singalongs.

I think that’s a struggle for a lot of kids’ artists. How do you balance the market against what you really want to do?

Definitely, but that struggle doesn’t come across in the Dees’ music. I started thinking about this question while I was listening to Strange Dees with my kids, and after “The Golem” came on, I had to spend a few minutes explaining Jewish history to them. It’s one thing to be educational, but these songs are conversation starters, and I get the feeling that that makes some parents uncomfortable — particularly now, when so much children’s entertainment is soft and round and perfectly bite-sized.

I personally have always liked stuff that invites me to do more research. As a young music fan, I was always the kid who’d get into Led Zeppelin, which sent me back to Willie Dixon, and so on. To the point where I was like, “Oh, you listen to Zeppelin? That’s lame. Listen to this.” It’s the same with songwriting. I never want it to come across like “Let me tell you the whole history of this.” People tell me that would be good because it would help kids with tests, and that’s a valid thing, but it isn’t really where my talent lies.

I want to get kids excited about history and other academic areas, and if they want to take it further, we have suggestions for books they can read. But I don’t want to be that guy who stands up there and lists things off. People are always telling me I should write a song about, you know, the state capitals. Maybe I will.

It’s much more interesting, I think, to be dropped into the middle of the story and be invited to figure out the rest on your own. But that’s decidedly not the norm. People seem to expect things that are more easily digestible in bite-sized chunks, and this doesn’t really fit that mold.

And that’s been my struggle ever since the band began. I’ve always thought we were doing really good work, and been frustrated by the fact that it seems like people would rather hear traditional children’s songs, or songs about more traditional children’s subjects.

How much thought, if any, have you given to what might come next for the band?

There are a couple of things I’m batting around. One is sort of a personal history project — you know, on this record, we have “Mayor LaGuardia’s Stomach,” where our guitarist Ari listens to his grandmother tell her story. I’ve thought about doing a record that’s all that kind of thing. Maybe people who are more well-known, like Abigail Adams, but songs based on those personal stories. Collecting them in that way.

You’d be the Studs Terkels of kindie!

Right, right. One of our fans is one of the founders of StoryCorps, and I’ve talked to him about legal stuff — how you clear those rights to people’s stories. We’ve also talked about doing an Old Testament record, which might sound crazy. But Chris, our multi-instrumentalist and my main partner in the band, is a church choir director. That’s his day job, and he’s always bemoaning the fact that all the music that’s published for children and free for use is pretty bad, so he’s always using older public domain stuff, and he’s forever after me to write some songs in that vein.

I think the Old Testament stories fit pretty well in the vein of the Dees. We can approach them as tales. We also did a few traditional songs for Scholastic a few years ago, and they didn’t put their legal team on it until after the recordings were finished, and they figured out there were some unplanned publishing fees and they shelved our stuff. They’re there, and this would build on that. I don’t know if we’ll do either of those things, but they’re the two ideas that appeal to me the most right now.